Hashing Positions #

Solving a game means exploring an enormous game tree. This can be computationally expensive to compute every time we want to play the game, especially for bigger games. To avoid recomputing positions over and over, we need a way to name each position with a number so we can store and look it up quickly. That “naming function” is our hash function.

Big Idea: Memoization #

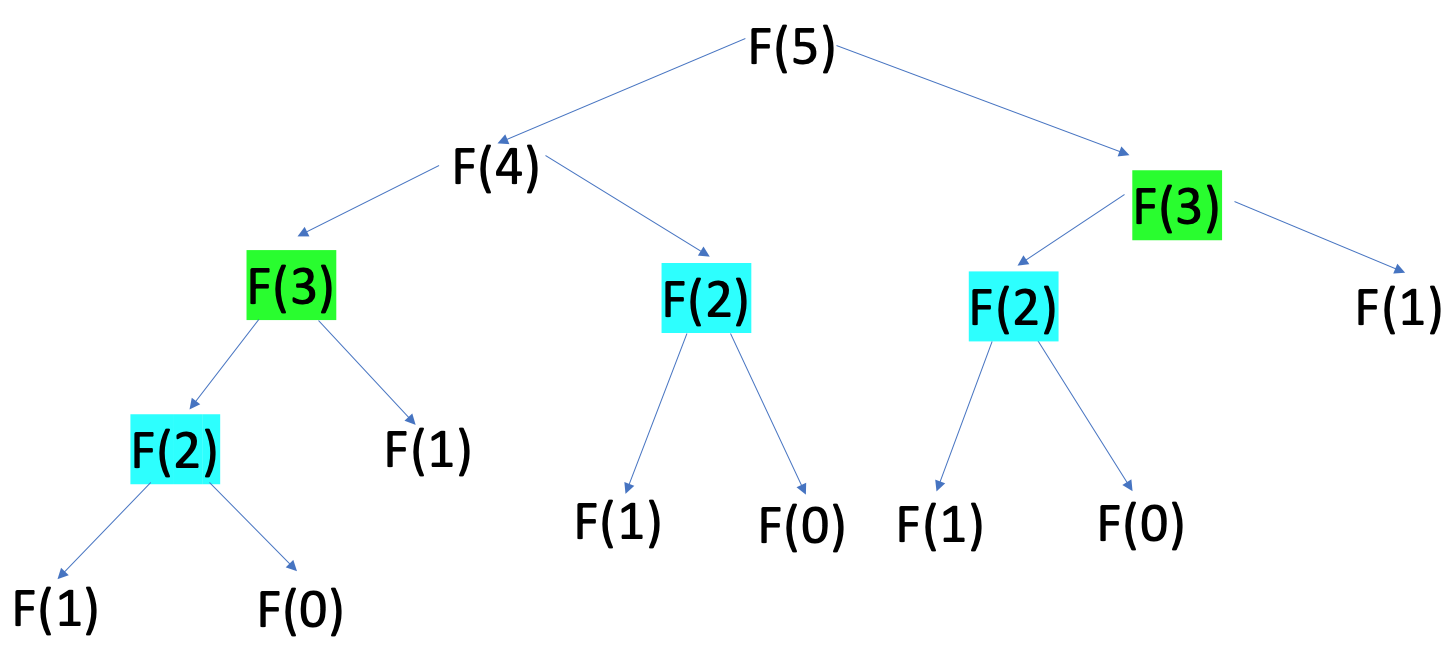

Our solvers use memoization to be more efficient. This means that, once a position has been evaluated, we store its value instead of recomputing it. This is just like caching Fibonacci values instead of using recursion to find every value. We can illustrate this with a simple Fibonacci function. We can access previously computed values by storing pairs (n, fib(n)) in a table.

int fib(int n) {

if (n == 0 || n == 1)

return n;

else if we've already computed fib(n):

return stored value;

else

int value = fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

store(n, value);

return value;

}

For games, we can’t use a simple number to store a position’s value. We need to represent the entire board state, including whose turn it is, where the pieces are, and so on. How do we map this data into an integer that will serve as an index into our table? This mapping function is called a hash function.

What Is a Hash Function? #

A hash function takes a piece of data (like a board) and returns an integer. We use that integer as an index into an array or as a key in a table.

For our solvers, a good hash function should:

- Map each reachable position to a unique integer

- Spread different positions out evenly across the table

- Be fast enough to compute on every recursive call

Writing a Tic-Tac-Toe Hash Function #

Let’s consider how we might write a hash function for Tic-Tac-Toe. Here’s how you play:

- One player chooses X, the other chooses O

- Two players take turns placing Xs and Os on a 3×3 grid

- Assume X goes first

- Once a piece is placed, it isn’t moved

- The first player to get three in a row wins

- If the board fills up with no winner, it’s a tie

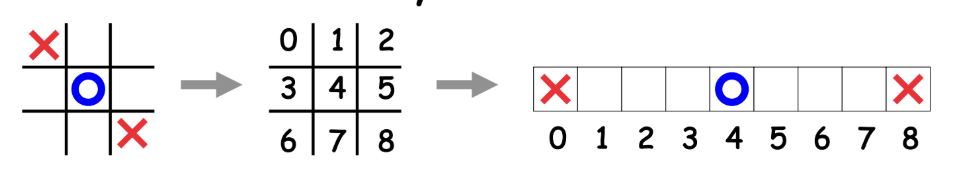

How do we convert a Tic-Tac-Toe position into a unique integer? One idea is to turn the 2D board into a 1D array of 9 slots:

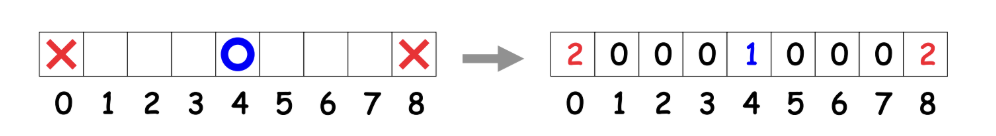

Each slot can be in one of three states: blank, O, or X. We can represent these as three numbers instead:

0for blank1for O2for X

If we treat this as a base-3 number (a “ternary” number), we could hash a position by interpreting the 9-digit ternary number as an integer. That gives us up to 3^9 = 19683 possible codes.

Optimizing the Hash Function #

If we understand the rules of the game, we can do better than just using all 3^9 possible combinations. For Tic-Tac-Toe:

- Players alternate turns

- X always goes first

- You can never have more than one extra X than O on the board

This means many of the boards our hash function can encode are impossible in real play, like boards with 5 Os and 1 X.

We can count the number of legal boards using combinatorics. Let s be the number of slots.

Small examples:

s = 1: 2 boards (-,X)s = 2: 5 boards (--,-X,X-,XO,OX)s = 3: 13 boards

This pattern continues based on how many Xs and Os are allowed at each depth.

Using Combinations #

For example, the number of ways to choose k locations from n is:

n choose k = n! / (k! (n - k)!)

This lets us count valid arrangements of Xs and Os.

Blur Method #

- Choose locations for all

x + opieces:C(s, x + o) - Choose which of those positions are Xs:

C(x + o, x) - Multiply both together.

Overcount Method #

- Count all permutations:

s! - Divide by repeated symbols:

x! o! (s - x - o)!

Both methods give the same result.

Using this method for full Tic-Tac-Toe, there are only 6046 legal boards, not 19683.

Finding a New Hash Function #

We can use bias + rearrangement to produce a combinatorially optimal hash:

Bias (offset)

Count how many legal boards exist in all layers before the current one.Rearrangement

Rank positions within the current layer using combinatorial counts.

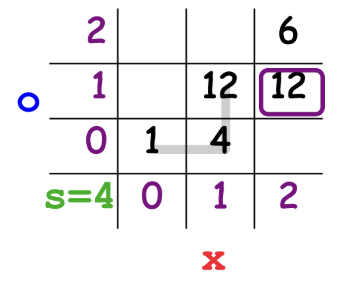

Example: Hashing a Small Board #

Suppose we hash the toy board: XO-X (4 slots).

Bias:

IfX = 2,O = 1,S = 4, count how many boards come before this layer

Example:1 + 4 + 12 = 17Rearrangement:

Count how many legal rearrangements come beforeXO-Xinside its layer

Example:3 + 3 + 2 = 8

Final hash:

hash = bias + rearrangement = 17 + 8 = 25

Practical Considerations #

Combinatorially optimal hash functions are powerful, but they can be expensive for larger games. In practice, we often use simpler hashes that are:

- Easy to compute

- Well-distributed

- Low-collision

We can also use symmetry (rotations and reflections) to reduce the total number of stored positions.

Summary #

- Memoization saves time by remembering solved positions

- Hash functions map complex positions to integers

- Combinatorial hashing packs only legal boards into small ranges

- Bias + rearrangement builds optimal hashes

- In practice, we balance optimality with efficiency